Translation by Mirta Roncagalli

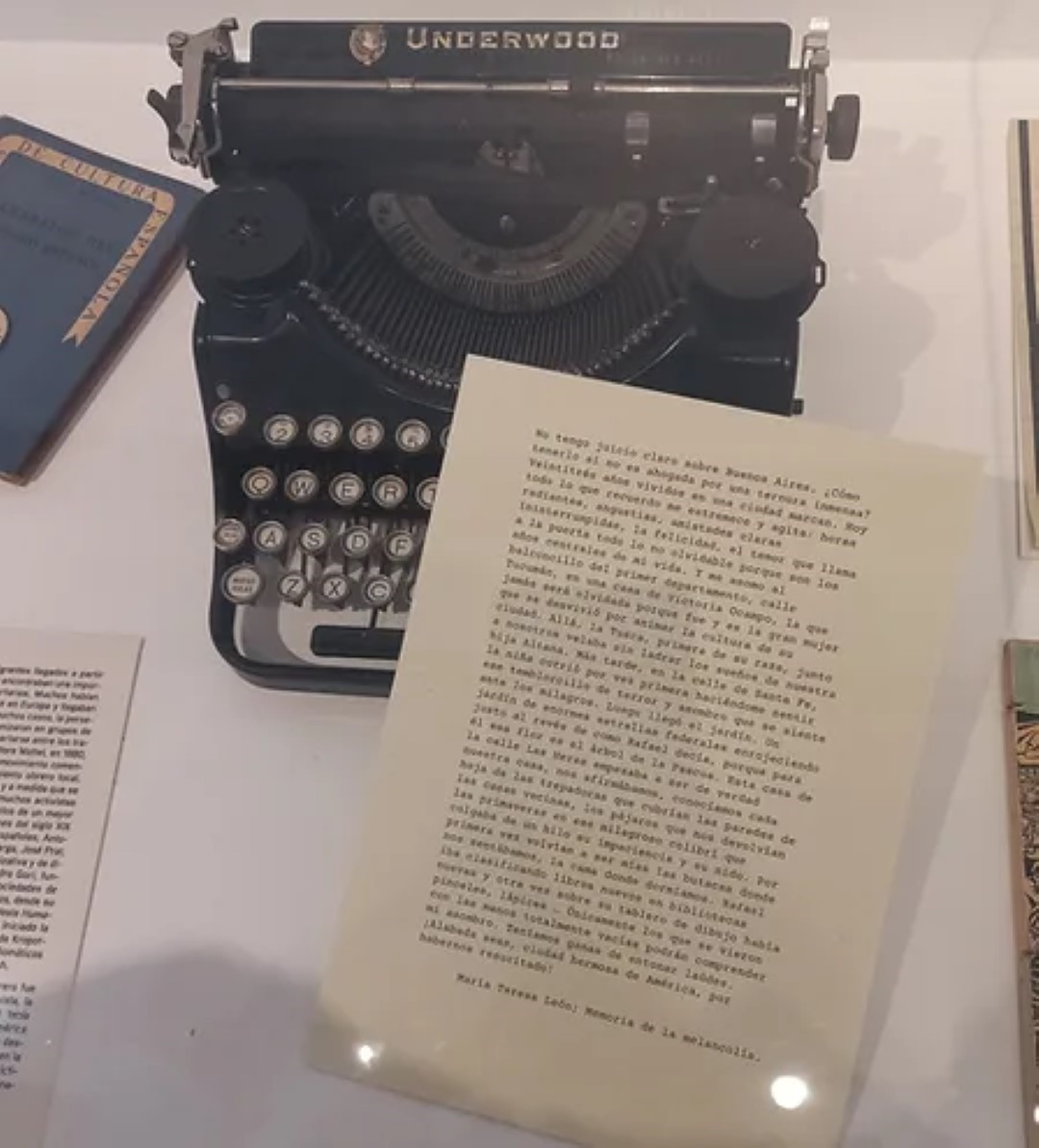

This typewriter belonged to the Spanish poet Rafael Alberti, who came in exile to Argentina as a result of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

Writing is a central aspect of migration. Migrants use it maintain connections with the land and the people they leave behind. Historically, they also wrote about personal experiences and feelings in diaries that they rarely shared. For many, writing could be a daily refuge to reflect on or unload about negative and positive experiences.

In letters home, people could narrate their journey: if they had found a job or not, if they were feeling comfortable in the new society, what new and unknown elements captured their attention. Likewise, the epistolary exchange, filled with details and affection, kept the promise of a family reunion. Although illiteracy was high, that didn’t prevent migrants from engaging in reading and writing. For example, those capable of reading and writing acted as mediators, and they wrote letters on the behalf of others or read aloud the letters that a friend received.

This typewriter represents a specific connection between exile and writing. On display at the Museo de la Inmigración in Buenos Aires, it evokes the image of a great many writers who had to choose exile in the first half of the twentieth century. The flourishing culture of epistolary exchange was also a space where authors narrated the sorrows of exile. Contact with people elsewhere could help. In those difficult times, exiles – often poets, scholars, and intellectuals – found shelter in writing.

Rafael Alberti was one of those writers who arrived in Argentina looking for shelter and who encountered what he called “networks of hope”, a group of friends, intellectuals and active members of the local culture that welcomed him and let him continue his literary work. Writing offered many authors protection from fear, persecution and, at the same time, a job and livelihood.

Depicted in the picture in a short message in the typewriter is a fragment of “Memorias de la melancolía” a moving autobiography in which María Teresa León, writer and wife of Rafael Alberti, recounts the experience of exile. The path that this couple followed from Spain to France and then to Argentina was marked by the nostalgia that the exile brought, a path where writing was a great ally.